The Future of ICT Requires You to Tear Down Walls

The evolution of information technology enables a new organisational structure within information and communication technology (IT) groups, one that mimics a pattern common among mature industries such as automobile manufacturing: the network organisation. This article argues that by moving toward a network model, corporate IT groups can enhance their own responsiveness, improve alignment of business and technology strategies and establish themselves as a crucial and leading department of the modern enterprise.

Introduction

Species that adapt go on to produce new generations, while those that do not end up extinct. Corporations follow a similar path. Those that respond to threats and capitalise on opportunities become leaders, while those that struggle with change end up as historical footnotes. Successful evolution of an entire organism – be it a plant, an animal, or a multinational enterprise – is inextricably linked to the successful adaptation of its constituent parts. By embracing evolving technology and advancing corporate strategy, information and communication technology (IT) groups have the opportunity to leave behind their reputation as cost centers and establish themselves as leaders (and perhaps revenue producers) within successful enterprises.

Understanding existing structures and their determinants provides a basis for evaluating new alternatives. Therefore, this article begins with a brief review of traditional models of IT structure. Next, it examines five factors that lead an IT organisation to adopt a particular form.

Technological evolution, combined with credit tightening and ongoing cost-reduction initiatives, threaten existing IT organisations. Consequently, adaptation seems a matter of survival. Given this pressures, the article proposes several alternative structures for the network IT organisation and concludes with a four-stage roadmap that establishes a path forward.

Traditional Models of IT Structure

In general, IT organisations are responsible following functions: computer operations, communications/networking, emerging technologies, planning-technology, planning-applications, systems development, and end-user computing support. It is the change in locus of responsibility for these functions that characterizes differing IT structures. For instance, if all of the aforementioned functions are performed by decentralised groups within the company, a decentralised IT structure is being employed.

Within the field of information systems, there has been considerable debate regarding the need to centralise or decentralise IT resources and IT responsibility. Admittedly, there are advantages and disadvantages to either choice, and certainly no one choice is applicable to all organisations. Moreover, even firms that choose to centralise their IT resources are still likely to have several decentralised elements. The table below briefly summarizes how the various organisational forms have been operationalised.

| IT Structure | Description |

|---|---|

| Centralised | Responsibility for the IT activities within a corporation is held with a central authority, which is likely a corporate IT group. |

| Decentralised | Responsibility for the IT activities within a corporation is distributed amongst different lines of business and enablement areas. |

| Hybrid | Responsibility for computer operations, communication and networking, emerging technologies, and planning-technology (management of technology functions) is highly centralised. Responsibility for systems development, end-user computing support and planning-applications (management of the use of technology functions) is highly decentralised. |

| Re-centralised | Decentralisation of systems analysis and design, and centralisation of responsibility for strategy and operations. The hybrid model shares many similarities, but re-centralisation often follows large project failures and post-merger technology integration. |

Determinants of IT Structure

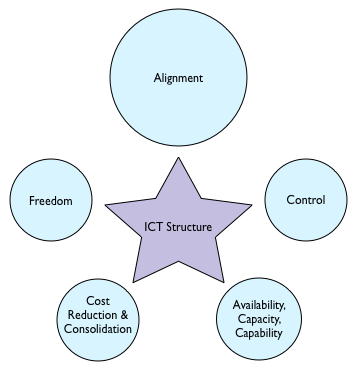

Why does one company employ a centralised IT strategy, and another company, perhaps even a firm in the same industry, use a decentralised strategy? There are five broad determinants of IT structure:

- Alignment with the model adopted by the enterprise

- The need (or perceived need) for greater freedom regarding IT deployments, standards setting, and operations management

- The need (or perceived need) for greater control regarding IT deployments, standards setting, and operations management

- Cost-reduction and IT-consolidation initiatives

- Resource availability, capacity and capability

Organisational Alignment

The structure of most IT organisations is often a historic artifact, enforced by corporate culture. When mature institutions such as banks began to deploy technology, centralised mainframes were their only option, so they were compelled to centralise IT resources. Consequently, even as their IT organisations evolved, they stuck with what they new: centralisation. In contrast, younger companies found themselves with no such legacy, quickly adopted PCs and commodity servers and spread their IT organisations to support the distributed technology.

The Need for Freedom

Some IT organisations may pride themselves on their heterogeneous platform, carefully built from best-of-breed packages and custom-built components. As these organisations mature, many of them continue to follow a similar approach. Such decentralisation grants users the technology they feel will best enable their success. In environments where creativity is crucial and IT requirements vary significantly between segments of the user population, there will be a tendency toward decentralisation of the IT function.

The Need for Control

Heavily regulated industries benefit from relatively homogenous architecture and infrastructure because it simplifies compliance with legal requirements and enables all users to receive standard service. Although heavily regulated industries often have heterogeneous IT landscapes due to legacy investments, from a temporal perspective, they generally aim for standardisation. Since most heavily regulated industries are not known for their creativity, providing a common platform has little impact on the ability of users to perform their jobs. When the need for control is high, there will be tendency toward centralisation of the IT function.

Cost Reduction & Consolidation Initiatives

Changes to organisational design are rare because the require to people, processes and technology are disruptive and distracting. Since it’s often difficult to quantify the benefits, firms only infrequently embark on such journeys, and then often do so with reluctance. Nonetheless, structural changes can help address systemic problems, speed consolidation of acquired assets (post-merger integration) and support cost-reduction programs. However, many firms overlook the complexity of such transformations and end up abandoning plans or retrenching following initial disappointment. The re-centralised IT structure can actually be characterized in this manner: recognition of a sub-optimal situation and subsequent retreat to a familiar, if only temporary alternative.

Resource Availability, Capacity and Capability

Although some IT organisations may aspire to a decentralised structure, resource shortages, capacity constraints and capability deficits may curtail their plans. Although decentralisation provides greater agency to the user community, it results in duplication, requires more staff, and complicates efforts to provide timely business intelligence. In an environment where skilled staff are difficult to recruit, where existing employees are already fully burdened and where current teams lack the necessary skills to support the enterprise, a centralised IT organisation allows mitigation of risks. By centralizing IT functions, staff can better support one another, freeing time for crucial activities like training and education.

Although all five factors mentioned above work to inform organisation design, desire for alignment is the most powerful. As organisations reorganize to outsource functions that are not deemed core competencies, they increasingly take on the feel of a network organisation. In order to preserve alignment, IT organisations require a corresponding structure.

The Network IT Organisation

American business history has seen the emergence of four broad forms of organisational structure: functional, divisional, matrix, and network. Most research concerning the structure of the IT organisation has dealt primarily with varying degrees of centralisation or decentralisation, but has paid little attention to alternatives. Supported by technological innovation, it is now possible to employ a network design for the IT organisation itself. The proposed network IT organisation marries concepts from organisational design to components of centralised, hybrid and decentralised computing. More specifically, it extends the hybrid structure by modularizing the IT organisation to enable teams to focus on services and respond to emerging demands with agility.

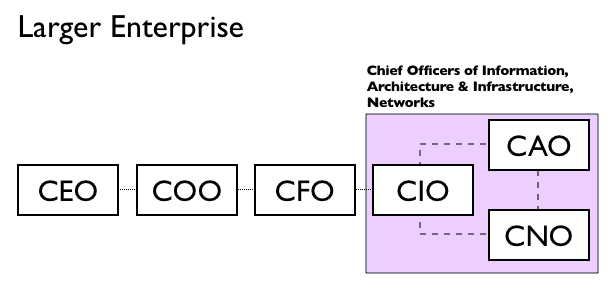

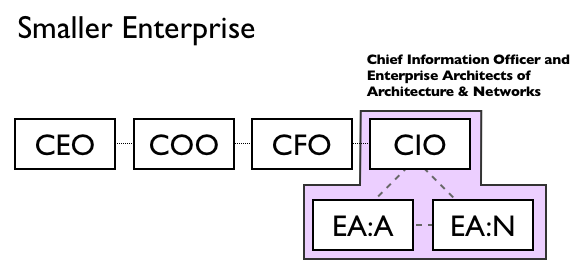

New Executive Roles

Responsibility within corporations is generally divided among the familiar roles of CEO, CFO and COO and CIO (and perhaps others, depending on the size of the organisation). To facilitate adoption of the network IT organisation, responsibilities once held solely by the CIO must be shared with a new cadre of architects responsible for platform architecture and infrastructure, and the various networks through which partners will support the business. Within large organisations, where technology plays an essential role in the business, these new roles should be created at CxO level (Chief Architecture Officer and Chief Network Officer). Within smaller organisations, or within firms that rely less on technology, Enterprise Architect: Platforms and Enterprise Architect: Networks, would be suitable. In either case, the staff would work directly with the CIO to provide dedicated attention to:

- Information

- Platform and software architecture

- Network architecture

New Responsibilities

Critical functions such as strategy formulation, infrastructure design, and technology evaluation remain centralised, within the purview of CIOs and their architects. The team also accepts responsibility for creating a future-state architecture, decoupling existing systems and then identifying which of them can be migrated into the hands of distributed partners.

Some members of the IT organisation will undoubtedly balk at migrating parts of their operation to partner agencies. Notwithstanding their trepidation, if one accepts that the IT organisation’s first responsibility is to serve the business, then one should also accept that it is the organisation’s responsibility to provide the best possible service. If external firms are capable of providing a superior product, then the IT organisation should employ them. The table below describes how primary IT functions might be operationalised in the context of a network organisation.

| Function | Operationalisation |

|---|---|

| Computer Operations | Computing services are organized in a distributed co-operative manner. Shared resources are both centralised and decentralised, depending on locus of expertise. All equipment is administered and maintained centrally. |

| Communications & Networking | All equipment is maintained by decentralised groups, and is purchased based on centrally established standards. All administration is performed centrally. |

| Systems Development | Purchased software is used where possible. Through consideration of group requirements, development standards and methodologies are created and maintained centrally. Decentralised groups then use the centrally maintained toolbox to perform specialised application development. The development lead is determined by locus of expertise, and could feasibly include external developers for projects where critical skills are not present internally. |

| End-user Support | Support is performed by decentralised groups based on the locus of expertise. All users rely on the same centralised issue-management system, parts of which are also available to users who may search for ways to addresses their own problems before reaching out for assistance. |

| Emerging Technology Evaluation | Scanning and reviewing emerging technologies is performed centrally, where new innovations can be quickly evaluated as solutions to challenges faced by the enterprise. |

| Planning Applications | Application planning is performed centrally for enterprise applications, and by a decentralised multi-group team for specialised applications. In both cases, teams follow enterprise architecture standards and evaluate managed (Software-as-a-Service) offerings. |

| Planning Technology | Using input from decentralised groups, and transaction information from equipment (storage space used on servers, packets forwarded by routers, etc.), technology plans are developed centrally based on business strategy and vision. |

The Road Ahead

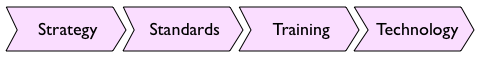

Parceling responsibilities between individuals is an exercise in theory. By clearly demonstrating how such a division can be implemented within the context of an IT organisation, this article strives to provide a concrete path forward. The section below presents a four-step framework for moving IT organisation toward a network design.

Strategy

Regardless of the point from which the IT organisation embarks, if its path diverges from that of the business, turmoil lies ahead. Therefore, before attempting to transform a bureaucratic centralised organisation into a nimble network organisation, consider both the goals and the structure of the broader enterprise. Answer these questions:

- What are the strategic goals of the enterprise?

- What are the strategic goals of the IT organisation?

- Are the enterprise and IT goals in alignment? Will enterprise strategy be supported by a network IT organisation?

- What organisational structures are employed by the broader enterprise?

- How receptive is the organisation to change? Do senior leaders outside IT support the transformation?

If enterprise and IT strategy are not aligned, or if the change is unlikely to support the corporation’s ability to achieve its strategic goals, expect to find little support for the transformation. Similarly, if no other division in the corporation employs a network structure and if the organisation is generally resistant to change, the IT organisation isn’t likely to find many cheerleaders when it presents senior leaders with a business case for transformation. In the event that you find yourself in any of these circumstances, it would be foolhardy to invest further energy in the transformation. Instead, concentrate your energy on aligning corporate and IT goals, identifying barriers to progress and building a strong business case for the project. Demonstrating how the plan will enhance agility or reduce costs always make good starting points for a discussion.

Standards

When early hurdles have been cleared, and when members of the team understand strategic goals and their role in achieving them, the IT organisation can move toward expansion of standards. In this sense, standards doesn’t merely stand for a single brand of server or a single word processing application. It does include those things, of course, but extends those concepts to include the rejection of proprietary protocols, custom software and single-vendor equipment. By embracing open standards, IT organisations avail themselves of many new alternatives which can help improve productivity, enable strategic sourcing and cost consolidation and improve customer satisfaction.

Although many opportunities exists to embrace standards, starting small will enable teams to chalk up some victories and build momentum needed to tackle larger projects later.

- Standardize technology used across the enterprise. Start with PCs and phones, and then move to printers, copiers, servers, routers and telecommunication services. Where possible, adopt a single platform (e.g., laptops for everyone). Following such an approach enables development and distribution of a single disk image, and means teams can focus on solving a problem, rather than having to first learn new things. Where such standardisation is not feasible, investigate PC virtualisation offerings from vendors such as Citrix, VMWare and Microsoft. These products enable base image standardisation and distribution of application bundles to narrow segments of the user community. Focusing on a similar one-technology approach has been a key success factor for airlines like SouthWest and RyanAir, who rely on a single type of aircraft. Using the single-equipment approach, flight crew and maintenance staff move smoothly among all equipment, reducing delays and simplifying routine inspections.

- Create, adopt and refine processes for all technology related tasks such as account provisioning and deactivation, service-desk ticketing, procurement, life-cycle management and patching. By having standard processes (that are well documented!), teams become more flexible – institutional knowledge is no longer trapped in one person’s head – and opportunities for process automation present themselves. When automation opportunities exist, vigorously pursue them. A person adds no value when creating user accounts: automated processes manage the task much more quickly and consistently.

- Adopt tools to enhance processes. Beyond automation, using electronic tools to support tasks such as service-desk ticketing provides multiple benefits. First, tools provide agents with a structured process, allowing them to more effectively triage calls. Second, the tools capture and store details of the problem and its resolution, which makes it possible to expose the same data to users who might answer some of their own questions. Third, using tools simplifies the process of migrating services to partner agencies if they’re able to provide superior service.

- Measurement allows benchmarking against past performance and against industry peers. Using tools mentioned earlier, you’ll be able to track important metrics such as network load, processor utilisation, electricity consumption, service-desk call volume, average time to resolve tickets, and user satisfaction. These metrics help gauge progress over time, compare your results to competitors and assist with identification of processes that might be suboptimally structured. For instance, if measurement reveals that procurement requests take 3 weeks to complete, process evaluation might reveal that most of the delays are caused by a process that flows through a single person. Understanding the issues sets the stage for redesign.

Training

Training is important to the success of almost any initiative. Even something that seems inconsequential – upgrading the photocopier, for instance – is best accompanied by some training. That doesn’t mean holding day-long classes to show everyone all the new features of a copier. However, distributing a “cheat sheet” describing how to accomplish once-familiar tasks, or merely attaching the sheet to the copier saves time, saves paper and makes everyone a whole lot less frustrated.

If training is important to smaller projects, then it’s essential to the success of larger ones: bigger changes affect more people, fewer of whom were involved in the planning and execution. And, bigger changes affect people in more substantial ways than merely altering the way two-sided copies are made. With that in mind, examine the IT strategy and the projects that have fallen out of the earlier standardisation planning. Next, use a RACI chart to describe who will be Responsible, Accountable, Consulted and Informed for each of the project tasks. Ensure that anyone who is responsible and accountable for things is properly equipped. If not, ensure appropriate training is provided. Not only will a RACI chart (an sample for illustrative purposes provided below) help you clarify thinking on the projects ahead, but having the information will also be useful when presenting a case for larger training budgets.

Technology

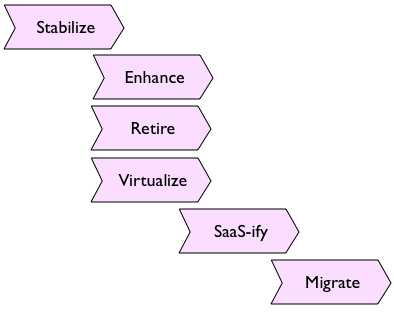

With standardisation projects underway – and perhaps some even winding down – it’s time to start evaluating how to dissolve the walls of the IT organisation. Fortunately, after moving through each of the stages, the organisation will be well positioned: the business and IT organisation share strategic goals, team members understand the mission, standards have been set and are starting to permeate the IT organisation, and appropriate training has been delivered. The next steps are more challenging because they’re significant and new, which means organisations will have do learn along the way. Success with technology adoption follows a 6-stage path.

- Stabilize. In order to create the network IT organisation, a reliable and stable IT framework must exist. Without a reliable system, little can follow, so address problems before moving forward.

- Enhance. Using the IT capacity plan and metrics collected during the standardisation initiative, identify shortcomings with the existing plans. If deficiencies exist, work to expand capacity as you begin retiring legacy components.

- Retire. With standards in place, IT staff can begin consolidation projects by retiring existing equipment per its life-cycle. It’s also a good time to look at contracts for services such as telephone and networks. As physical assets are retired, it might be time to let go of old service contracts, too. Reducing platform heterogeneity and consolidating contracts simplifies internal processes, and strategic sourcing reduces costs by consolidating purchasing power.

- Virtualise. One of the most crucial elements of the network IT organisation is virtualisation infrastructure. Severing the connection between a particular machine and a piece of software increases the IT organisation’s agility and opens up new possibilities. Briefly, virtualisation can simplify activities such as legacy application support, business continuity planning, and system test and evaluation.

- SaaS-ify. As equipment is retired and software reaches the end of its life-cycle, organisations are faced with the choice of running unsupported packages, upgrading to more recent versions or moving to a competing product. The first option can be risky, particularly if the software in question is important to the business. The second and third options can be costly and complicated. However, many firms have begun to mitigate these issues by hosting products in their own data center. The Software-as-a-Service model is a compelling alternative and should be considered where its available.

- Migrate. Of course, opting for a SaaS solution migrates IT components out of corporate data centers. Virtualisation also prepares firms for this step. As non-core services are identified, the virtual machine on which they run can be migrated (sometimes seamlessly) to external hosting facilities where they are managed, maintained and upgraded by another firm. One other frequently overlooked opportunity for migration is web-services. With powerful orchestration and choreography provided by enterprise service bus software, web services can also be migrated to partners.

Conclusion

With time, the IT organisation has become more like a business and less like an application development centre. Increasingly, it tends toward using standards to co-ordinate the output of internal and external groups in pursuit of a common goal: support of the business strategy and enhancement of the company vision. Accordingly, as businesses splinter themselves into collections of loosely connected entities, it’s important that the IT organisation have a complementary structure. What is especially exciting about the concept of the network IT organisation is that its flexibility allows many different permutations. There is no “right answer” for all companies; the malleable structure can be adapted to meet the specific needs of each organisation.

Many IT organisations have unknowingly begun the transformation, and it’s now up to them to clearly articulate their strategy and validate the network structure. With technology such as Amazon’s EC2, and S3, Google’s AppEngine and the array of “cloud computing” offerings that seem to spring forth regularly, it will be fascinating to watch the many different ways that companies operationalise the network model of the IT organisation. If you need help navigating your own path, I would love to hear from you.